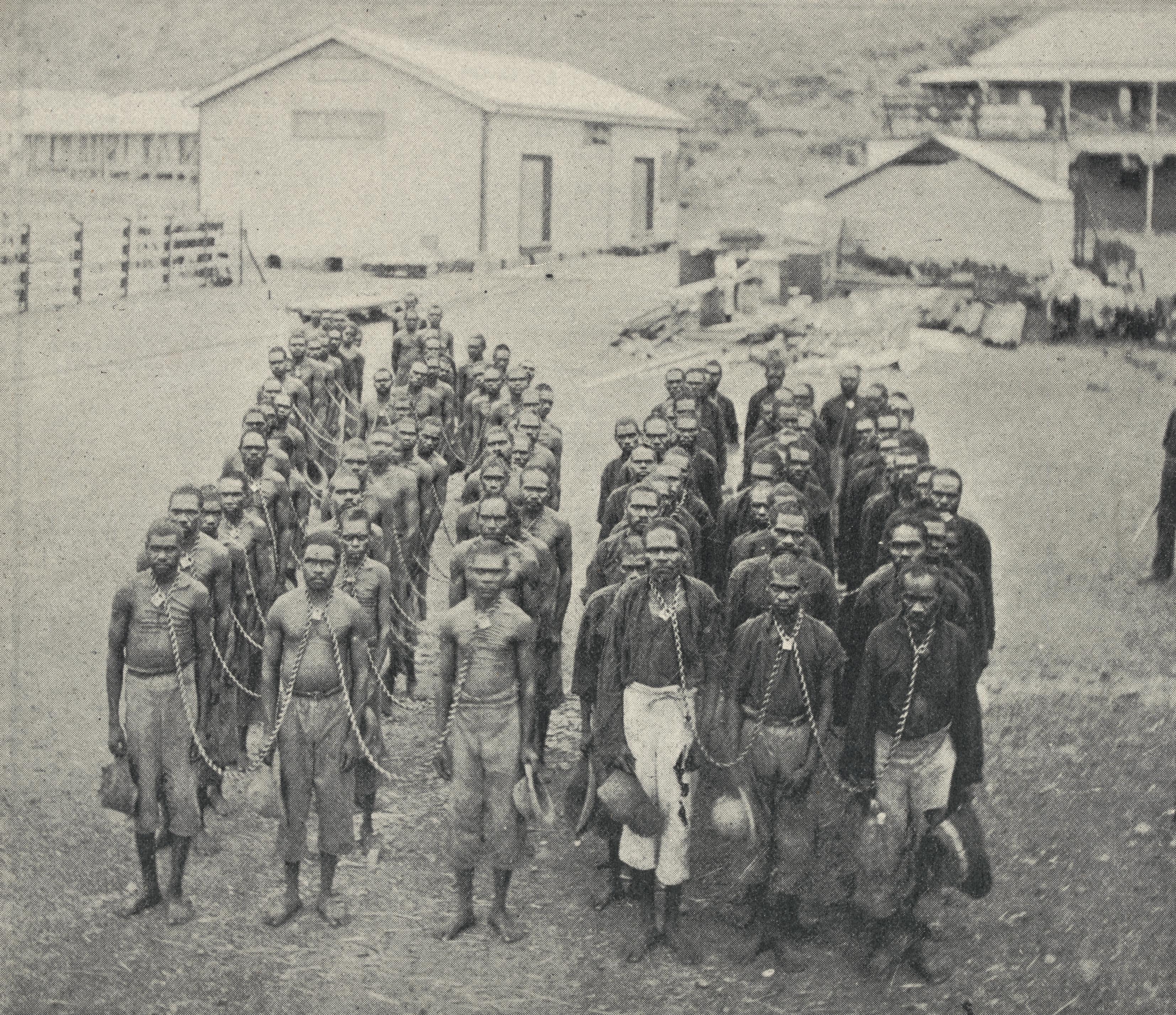

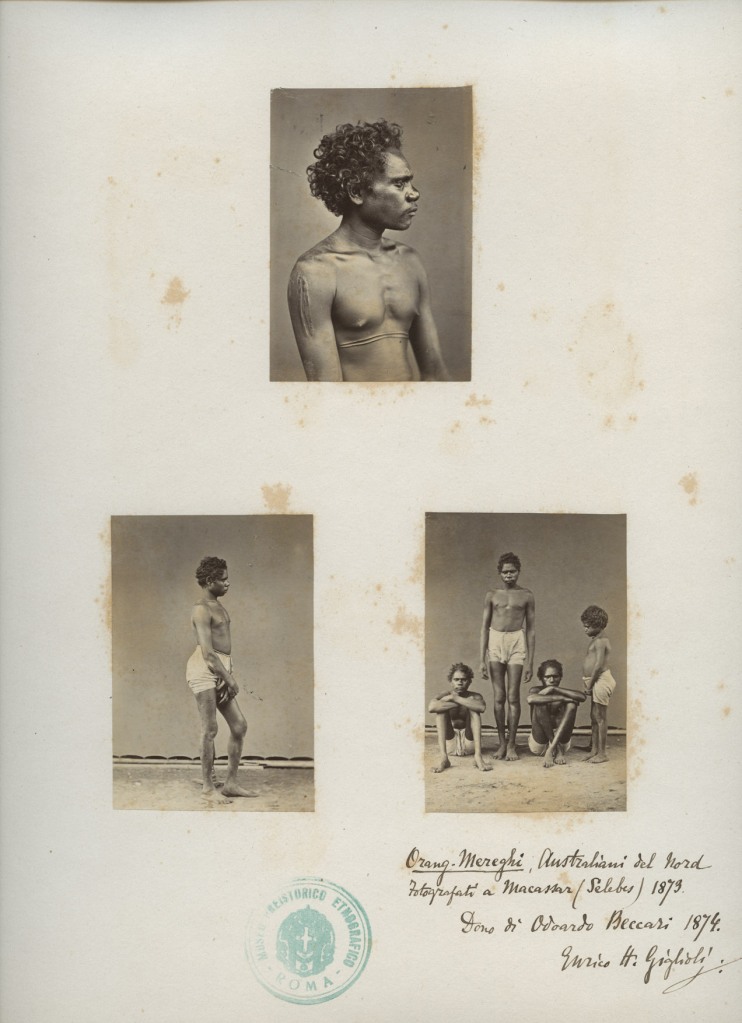

Odoardo Beccari’s 1873 Macassan photographs of the ‘Orang-Mereghi’

These photographs are an extraordinary trace of the centuries-old exchanges between Macassar and northern Australia – as their caption reads, they were taken in the port of Macassar in 1873, and show people of northern Australia – more precisely, from the Cobourg Peninsula. The history of the Macassan trade in trepang (sea cucumbers) with northern Australian Indigenous peoples is a rich and colourful one which has become of great interest to scholars and the public: part of its appeal lies in its exotic, cosmopolitan story of intercultural exchange, with its themes of reciprocity and Indigenous autonomy. Leaving Makassar in the province of South Sulawesi (Celebes) with the northwest monsoon in December, these trader fishermen with their crews of Makassan, Bugis, Butonese, Timorese, Malukan and Papuan sailors travelled to Australia. They called the Arnhem Land coast Marege, and the Kimberley coast Kayu Jawa.[i] This history challenges oppressive British-centred national myths of a fatal impact upon a pure and archaic race, emphasizing that Indigenous people were equals and participants in the Macassan trade rather than subordinate victims. It shifts our focus from the south-east, to northern Australia and its Asian connections.

I encountered these remarkable photographs in 2011, in Rome’s ‘Pigorini’ Museum- now the Museo delle Civilta- MPE “L. Pigorini”. – named after the nineteenth century Italian archaeologist and ethnographer. They are held in the photographic collection assembled by zoologist and anthropologist Enrico Hillyer Giglioli (1845-1909), who is remembered as a founding figure of Italian science.

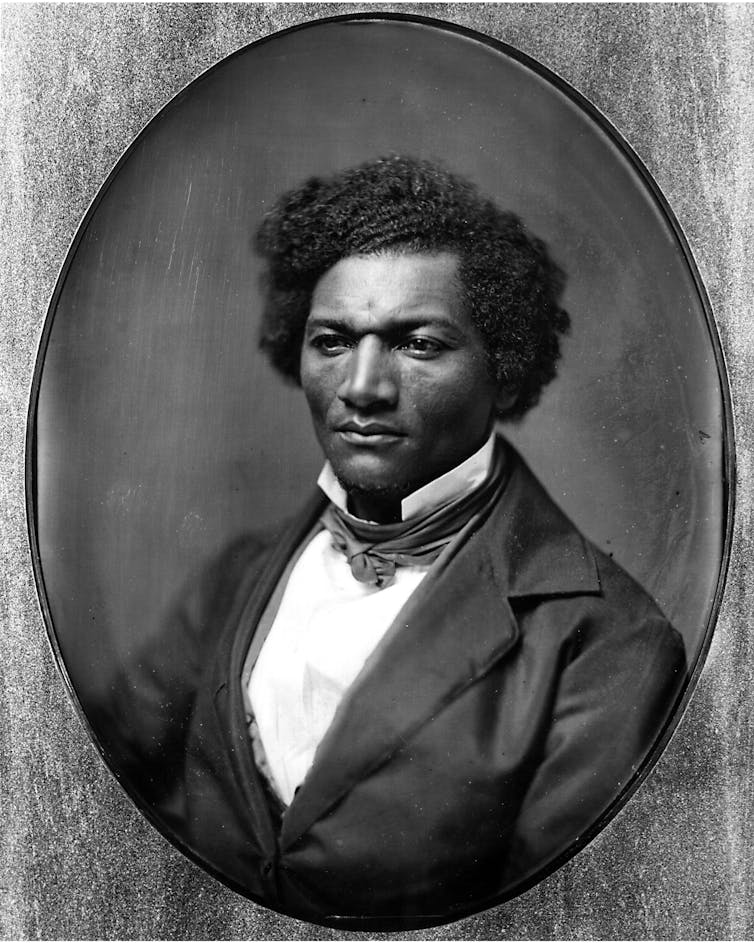

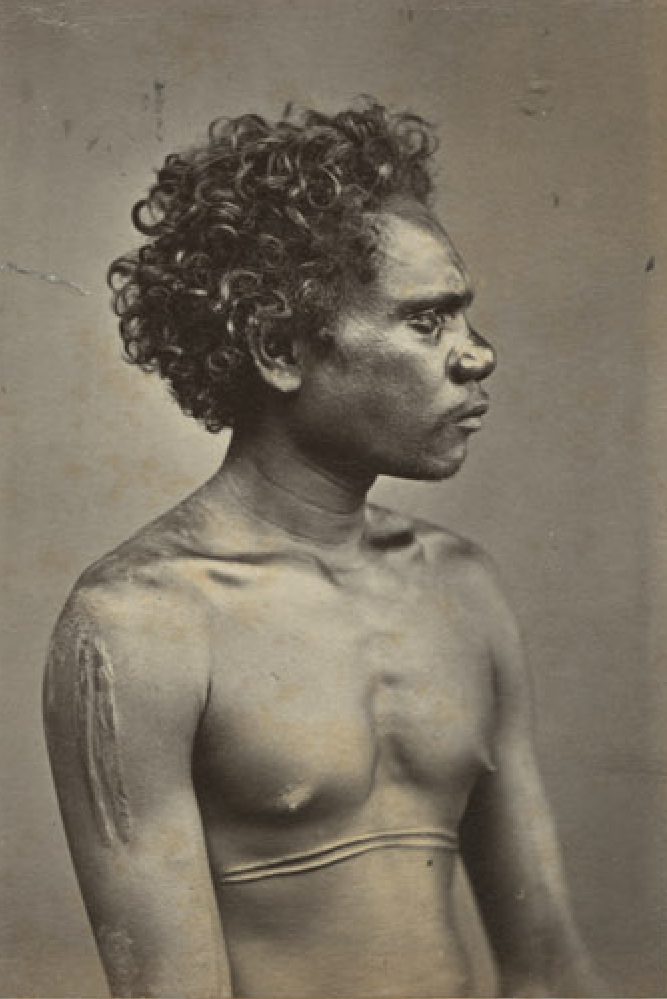

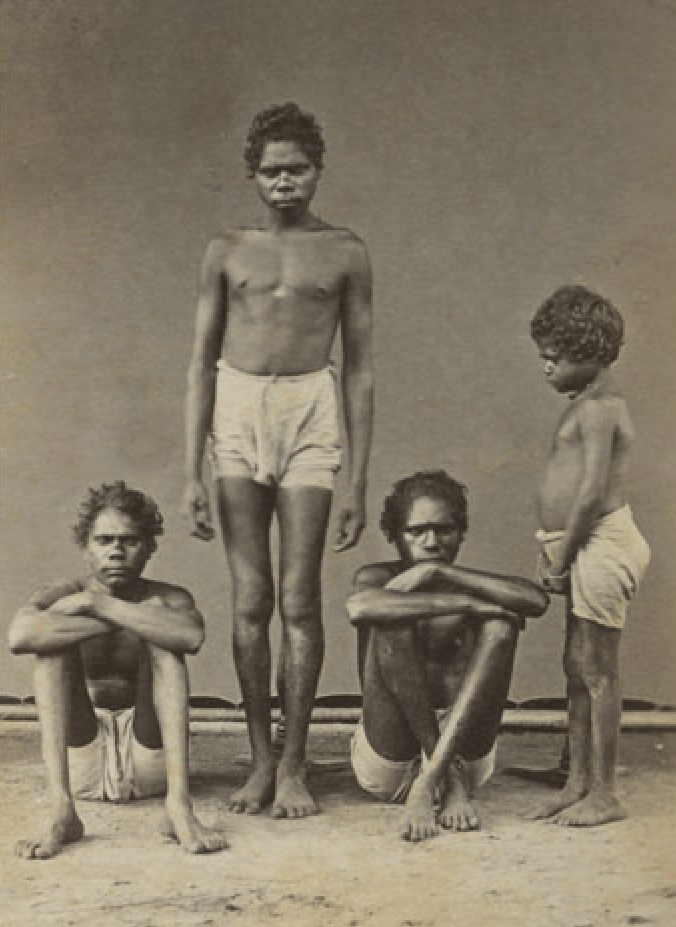

I had seen one of these photos reproduced as an engraving of an Aboriginal man in various nineteenth century publications, but when I saw the original photographic prints depicting Australian Aboriginal people I realised two things: first, that they were taken in Celebes and so were a result of the Makassan trade, but also that they show children as well as an adult, pointing toward the family connections that formed part of these regional networks. The top half portrait shows a young Aboriginal man in profile, his chest and shoulders marked by ceremonial cicatrises (scars) revealing his initiation into Indigenous maturity.

© Museo delle Civilta- MPE “L. Pigorini”, Rome. copia 4191.

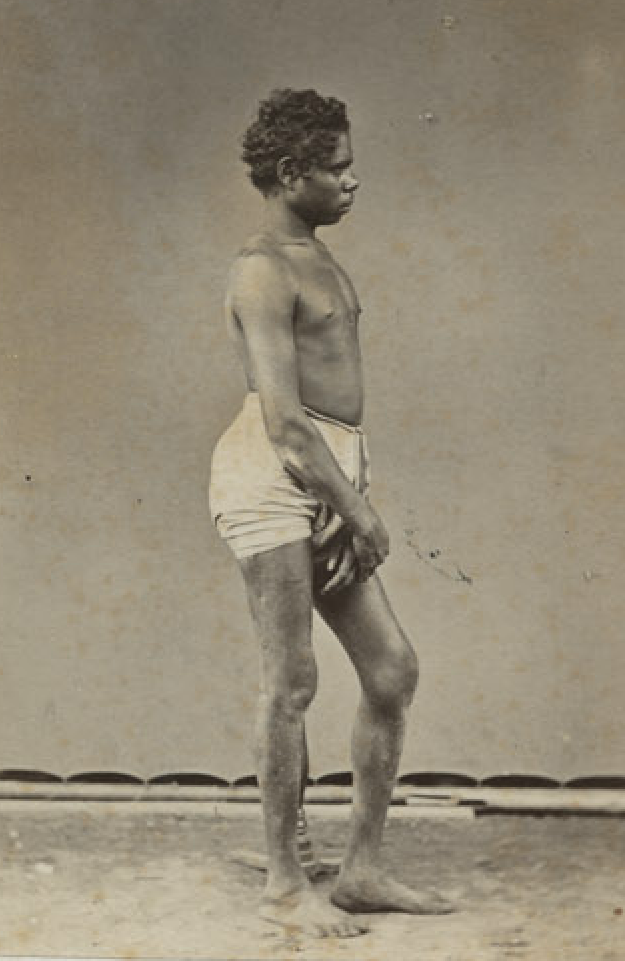

The lower left shows a younger boy, wearing a short length of fabric tied as a loin cloth, standing in profile, supported by a photographic stand. The lower right photo shows four boys, including the standing boy this time facing the camera; two more sit with their arms wrapped casually around their knees, while the fourth, a little boy aged perhaps around five or six, faces left, also supported by a stand. These last two photographs, at least, were taken at the same time, in a studio, as the standard backdrop suggests.

The lower left shows a younger boy, wearing a short length of fabric tied as a loin cloth, standing in profile, supported by a photographic stand.

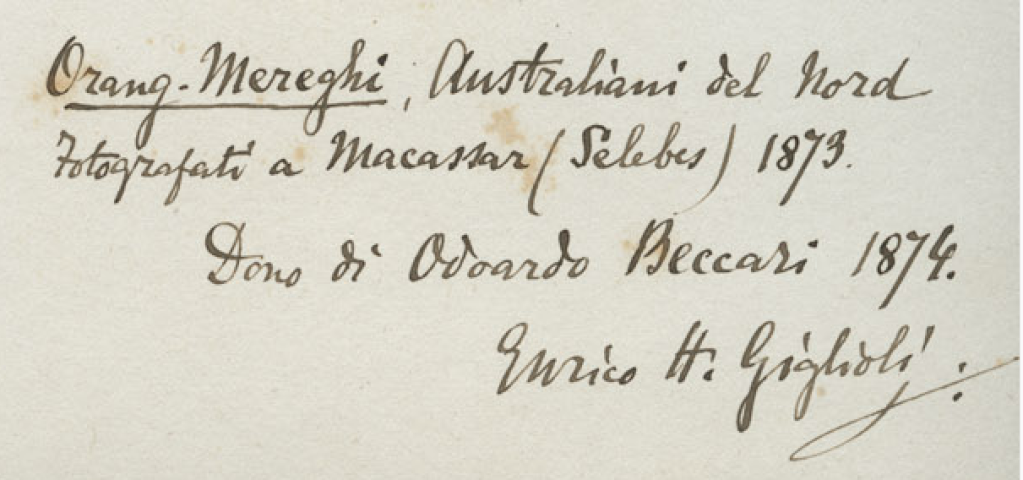

The lower right photo shows four boys, including the standing boy this time facing the camera; two more sit with their arms wrapped casually around their knees, while the fourth, a little boy aged perhaps around five or six, faces left, also supported by a stand. These last two photographs, at least, were taken at the same time, in a studio, as the standard backdrop suggests.Giglioli mounted these three prints on a large sheet of cardboard and inscribed the following caption: ‘Orang Mereghi, Australiani del Nord. Fotografati a Macassar (Selebes) 1873. Dono di Odoardo Beccari 1874. Enrico H. Giglioli.’ Translated, this means ‘People of northern Australia, photographed in Macassar in 1873’.

There are numerous accounts of this exchange by contemporaries, including from some Aboriginal people who actually participated in the trade. Charley Djaladjari from Cape Wilberforce on Elcho Island voyaged to Makassar around 1895, describing the presence of men and women who had settled and established families. Djaladjari told how the ship’s captain Wonabadi said to Deintumbo, ‘I’ve got some boys here’, and Deintumbo replied:

All right, I’ll take all these men, and they can come to my place to sleep and have food.’ He gave us money and we went with him. Near where I stayed several countrymen of mine were living. There was Jamaduda from the English Company Islands, who had come to Makassar as a small boy. He had worked there, and had never returned home. When I saw him he was a grown man: he had married a Macassan woman, and had four sons and four daughters. Then there was Gadari, a Wonguri-Mandjigai man from Arnhem Bay; he had come as a young man, worked there, and married a Macassan woman. When I met him he was middle-aged and had a lot of children there, but I heard afterwards that he had died. He had been married to an Aboriginal woman when he left the Australian mainland, and Duda is his son; but he didn’t return to his wife. I saw Birindjauwi, too; he was still unmarried when I left Makassar. I met a Ngeimil man, and many others as well. In the old days, before I went there, young unmarried men who came with the praus would often get married to the Macassan women and stop there; but usually the married men return home next season with the trading fleets. Sometimes young Aboriginal girls went to Makassar, too, but most of them stayed there to marry Indonesians or to work about the town.[i]

So the photographs embody these stories of movement and exchange, showing some of the people described by travelers – and possibly even some of Djaladjari’s named individuals, such as Jamaduda and Gadari, twenty years earlier. The boys may have travelled from Arnhem Land or been born in Makassar. The photographs are portraits which personify the individual biographies that are only fleetingly mentioned in other sources. This is the value that such photos have for Indigenous descendants more generally: they embody individuals and concretize family relationships. Biography has now become an important methodological tool for anchoring broader histories of global movement and exchange, instantiating sometimes abstract cultural forces. Photographic portraits offer a means to personalize larger currents of movement and exchange.

Why were these photographs made? As the inscription notes, they were given to Giglioli by his colleague, the Italian naturalist Odoardo Beccari (1843–1920) who had spent some years during the 1860s travelling through Malaysia, Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, where he described and recorded many species of plants. In 1872 Beccari travelled through the region to New Guinea, together with fellow naturalist Luigi Maria d’Albertis (1841-1901). Photography was an integral aspect of their collecting. In 1873 Beccari stayed in Makassar, and like other European observers, enjoyed its cosmopolitanism. He noted in his Nuova Guinea, Selebes e Molucche. Diari di viaggio ordinati dal figlio that ‘toMakassar come some “prahu” every year from Northern Australia, near the island of Melville, and Indigenous Australiansare not uncommon in Makassar where you see them moving about in the streets’. He explained that ‘in July and in September at the height of the influx, the harbour teems with boats of every type and size: Chinese, Malays, Indians,Bughis, Papuans, and Australians form a confused jumble of colourful turbans and multi-coloured clothes’.[ii]

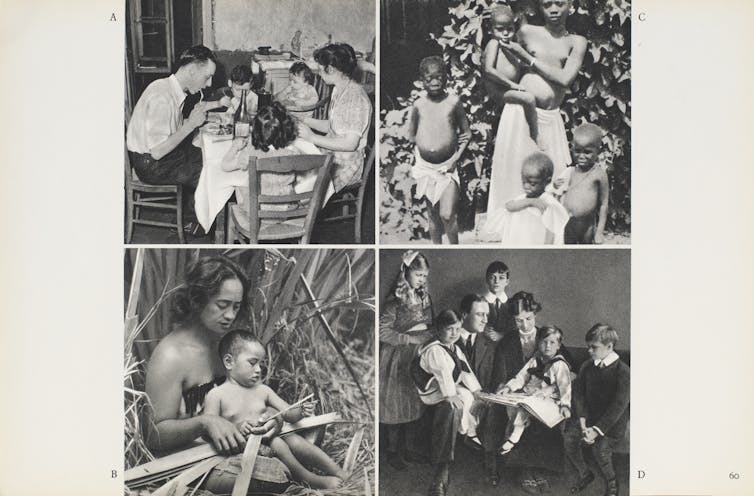

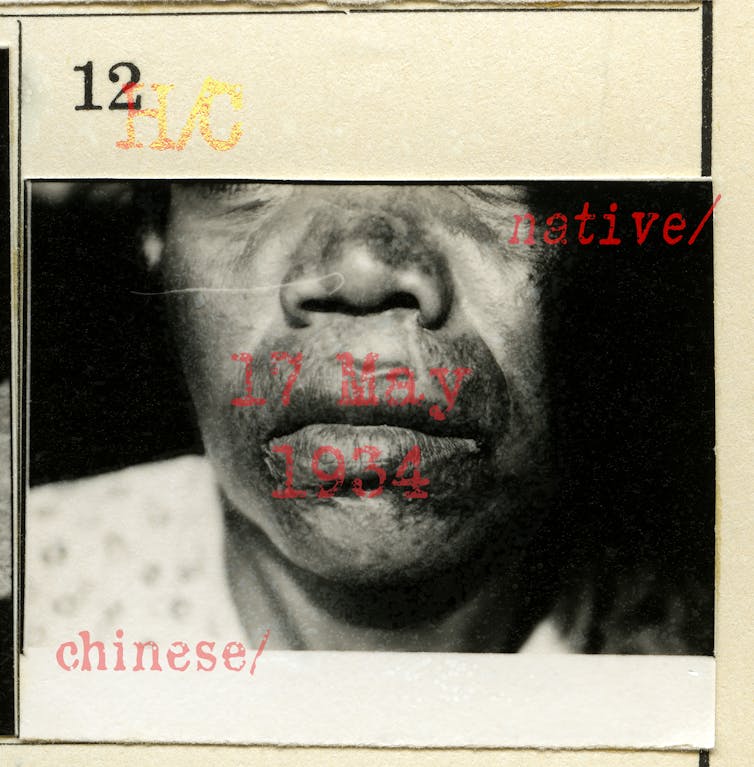

Perhaps this relish prompted his acquisition of the photos – combined with scientific interest, at a time when theories of racial difference were being consolidated. By mid-century, visual appearance was crucial for defining racial taxonomies, and by the late 1860s photography – especially the ‘portrait type’- had become a popular way of making human variation observable and real. Photographs of this kind, showing different human ‘types’, were often produced by professional photographers to satisfy the large market among scientists busy classifying the natural and human world. It is significant that the Australians’ appearance was considered distinct from both the Malay and Papuan populations, and this visual difference remained a theme. As early as 1824, the Dutch governor-general mentioned seeing Aboriginal visitors to Makassar, and noted that ‘they are very black, tall in stature, with curly hair, not frizzy like that of the Papuan peoples, long thin legs, thick lips and, in general, are quite well built’.[ii]

Beccari himself never published these photos, but his colleague Enrico Hillyer Giglioli made extensive use of then in both his books about Australian Aboriginal people, illustrated with engravings. Giglioli was a fervent Darwinist, having studied with Thomas Huxley as a young man, and experimented with visual evidence in arguing for affinities between Australians and other ‘Aryan types’ such as those from south India. However, he argued against a shared origin for Australians and Papuans, instead claiming that his portraits showed a homogenous Australian population. But he also acknowledged a link between northern Australian Aboriginal people and those of New Guinea on the basis of their facial form and profile, using the Selebes portrait as evidence, explaining, ‘I reproduce here the portrait of a native of this part of Australia, to be precise from the district of the Cobourg Peninsula’. He speculated that

This certainly does not show a Papuan but a true Australian aborigine, in whom the hair is curlier than usual. A strange fact is that Beccari is supposed to have seen similar people on the Aru Islands, where there are also true Papuans. Would they be the product of miscegenation between the two peoples? It is well-known that the Bughis have for many years regularly visited the North coast of Australia in search of tripang. They call this country Tanâ-Mereghi, and its natives Orang-Mereghi, often bringing them back to Makassar with them. It is more than probable that the natives of Melville and Bathurst Islands are similar to these and not to the Papuans properly so-called. The local variations between Australian aborigines known to me certainly do not amount to the differences presented by many other traces inter se, without any ethnologist feeling obliged to subdivide them. In conclusion I must add that the Australian aborigines have a word to indicate their nationality … On Cape York the aborigines, who have curled hair, call Australia Kai Doudai (small country) to distinguish it from New Guinea, from which they remember coming, and which they call Muggi Doudai (big country).[i]

Interestingly, Giglioli emphasised these ‘types’ as indissolubly fixed to territory – that is, Australia – ignoring the portraits’ origin in Makassar and its role in movement and exchange.

Even more ironic, the photos were made in precisely the time and place that were integral to the formulation of British scientist Alfred Russel Wallace’s (1823–1913) theory of evolution. Central to Wallace’s theory was the faunal discontinuity across a narrow strait in the archipelago now known as ‘Wallace’s Line’; this zoogeographical boundary extends between the islands of Bali and Lombok, and between Borneo and Sulawesi, and marks the western limit of many Australasian animal species.[i] Wallace noted the similarities of fauna in New Guinea and Australia as the basis for his argument that they once formed a single land mass (now referred to as Sahul). He extended his analysis to the region’s peoples, arguing that widely-scattered pockets of ‘woolly-haired people’ represented the remnants of a much more extensive population originally derived from Africa: ‘an early variation, if not the primitive type of mankind, which once spread widely over all the tropical portions of the eastern hemisphere’.[ii] Wallace argued for an absolute difference between Malays and Papuans – while Australians represented a different, Caucasian, race. Wallace was puzzled by the evidence for hybridity across the region, and his pursuit of pure racial origins led him to place hybridity in the very recent past. He interpreted such evidence in terms of the survival of ancient, essential differences still visible in the ensuing mixture, rather than the outcome of long exchange and local modification caused by natural selection.

In sum, evolutionist arguments about the essential differences between ‘races of men’ relied on assumptions that outer appearance expressed essential inner truths. So the Macassan photographs became scientific evidence for different human ‘races’. They were intended to demonstrate Aboriginal fixity – although an interpretation frequently destabilised by troubling perceptions of hybridity and exchange.

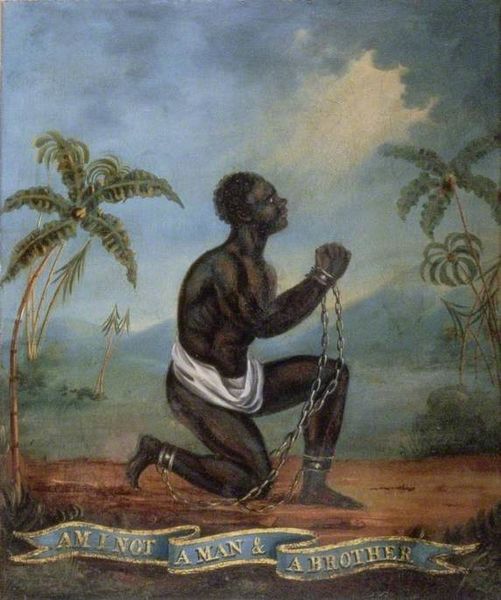

Such debates about human difference had profound political consequences. European evolutionism sought to define Indigenous Australians as primitive, with the effect of legitimizing colonial invasion and dispossession. More recently, the persisting colonial opposition between Aboriginal people as either static, primitive and authentic – or altered and inauthentic – has been used to constrain their choices and limit their claims to land and other rights. Recognition of Native Title, for example, demands the performance of Aboriginal identities centering upon an unbroken and fixed attachment to place. Yet by the same token, such difference is often construed as primitivism and incapacity, becoming the rationale for intervention and control.

By understanding the historical invention and political context for these ideas of ‘race’, we undermine its power in the present. These Aboriginal portraits therefore remind us of these oppressive ways of seeing Aboriginal Australians – but also their significance in asserting a deep history of a multi-cultural present.

To learn more about the history of these images see my chapter ‘Picturing Macassan–Australian Histories’, in Carey, J. (Ed.), Lydon, J. (Ed.). (2014). Indigenous Networks. New York: Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315766065

https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e/9781315766065/chapters/10.4324/9781315766065-7

[i] Alfred Russel Wallace, The Malay Archipelago: The Land of the Orang-utan, and the Bird of Paradise. A Narrative of Travel, with Sketches of Man and Nature (Singapore: Periplus Editions, [1869] 2008). This book was Joseph Conrad’s ‘favourite bedside reading’ and has never been out of print.

[ii] Alfred Russel Wallace, ‘New Guinea and Its Inhabitants’ (originally published in Contemporary Review, February 1879), The Alfred Russel Wallace Page, accessed July 16, 2012, http://people.wku.edu/charles.smith/wallace/S301.htm.

[i] Giglioli, Voyage Around the Globe, 797.

[ii] Quoted in Macknight, Voyage to Marege, 86, translated from G. A. van der Capellen, ‘Het journal van den Baron van der Capellan op zijne reis door de Molukko’s’, Tidschrift voor Nederlandsch Indië 17, no. 2 (1855): 375.

[i] They reached New Guinea in early December 1872 after visiting Java, Makassar, and the west coasts of Flores and Timor. In the Arfak Mountains in the northwest of what is now the Indonesian province of West Papua they collected zoological specimens, especially birds of paradise and ethnographic materials. D’Albertis’ cousin, fellow explorer Enrico Alberto d’Albertis, housed many of Luigi’s specimens at Castello D’Albertis. His natural history specimens from New Guinea are in the Natural History Museum of Giacomo Doria in Genoa. Luigi Maria D’Albertis New Guinea: What I Did and What I Saw. Vol. I and II. London: S. Low Marston Searle & Rivington, 1880.

[ii] Odoardo Beccari, Nuova Guinea, Selebes e Molucche. Diari di viaggio ordinati dal figlio Prof. Dott. Nello Beccari(Florence: La Voce, 1924), 268, 262.

[i] Berndt and Berndt, Arnhem Land, 56–7.

[i] Makassar was the heart of the Kingdom of Gowa. With its fine natural harbour, it was a chief trading port and situated on the crossroads of well-travelled sea-lanes, making it the gateway to Gowa.